Fast Fluid Dynamics

Fluids can be found all around us; everything from a glass of water to a wisp of smoke is governed by the laws of fluid dynamics. These laws are ingrained in us when we watch how a river flows or ocean waves crash. As a result, efficient and accurate fluid simulation is crucial for animating games and movies. For our final project we implemented an algorithm called Fast Fluid Dynamics (FFD) using Rust and WebGL. This is a method for creating real-time, stable fluid simulations that run entirely on the GPU based on Jos Stam’s paper, “Stable Fluids” (Stam 1999).

In FFD there are a few simplifying assumptions that are made. First, we assume that fluids are incompressible. This means that the volume of fluid in a given region in space (density) remains constant over time. Second, we assume that the fluid is homogenous or density is constant over space. Given these two assumptions we can apply the Navier-Stokes Equations for Incompressible Flow to model the state of the fluid over time.

Before we discuss the details here is a demo. You can find the code for it on my github here.

Navier-Stokes Equations for Incompressible Flow

Fluids are mathematically represented as vector fields; the vector field represents the velocity of the fluid at the point at time . Now, in order for the fluid created by to resemble one in our world the vector field must satisfy the Navier-Stokes equations for Incompressible Flow.

We won’t go into great depth how the equations work; however, we will discuss the terms of the first equation and how they relate to fluids that we observe everyday.

- The first term in the equation is advection. This is the process by which the fluid transports objects. For example, a leaf traveling down a stream.

- is pressure. This is the force exerted by a fluid on itself and its surroundings. An example of this in everyday life is the force that you feel when you pump a bike tire with air.

- The third term in the equation gives a fluid its thickness; this is what makes maple syrup flow less compared to water. The in the term is a measure of viscosity or how much the fluid resists flow.

- The final term, , is the sum of the external forces applied on the fluid. This could be anything from a rubber duck in a bathtub to wind on the surface of the ocean.

Fast Fluid Dynamics solves for these terms analytically given an initial vector field and computes the vector field at the next time step. In our implementation we simulate ink in our fluid; so, once we have the new vector field we use it to advect the ink to compute the next frame.

Fast Fluid Dynamics Algorithm

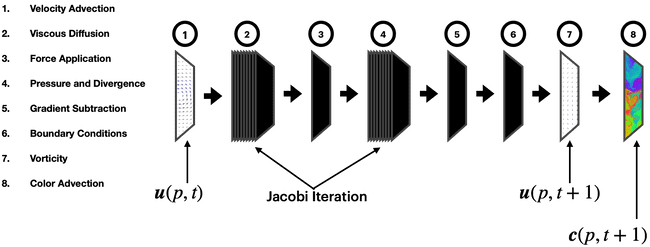

On a computer we represent a fluid as a 2D array of velocity vectors (or in the case of GPU, we use a texture). This representation is a discretization of the velocity vector field, . FFD uses this as an input and computes a new vector field by applying a series of passes over the original. Note that each pass specified by the algorithm iterates over each position of the 2D array; furthermore, each computation does not depend on a previously computed value. Therefore, they easily lend themselves to be executed on a GPU as a shader program.

In our implementation, these passes are fragment shaders written in GLSL. The velocity vector field is stored as a floating point RGB texture that is passed as a uniform to each shader program; the new vector field is then rendered to another texture. In order to be efficient, each pass has two textures which alternate as input and output. After we output the final velocity field, we advect the color field which is ultimately rendered to the screen.

Shader Programs

The first pass is to advect the velocity vector field. The new velocity at a given position is ; in other words, we look at where the value would have originated from in the previous time step. This advection pass is reused at the end in order to advect the ink in the fluid before it is rendered to a screen.

Second, we take the output from advection and then apply viscous diffusion. This pass takes in a viscosity parameter and “dampens the velocity” to model a viscous fluid resisting flow. This pass is computed using Jacobi Iteration, a numerical method to iteratively solve for a system of equations; therefore, this pass is actually made up of many passes that compute each iteration on the GPU. The number of iterations is also a tunable parameter.

External forces are applied next. In our implementation, only the mouse introduces force to the fluid. We compute a force proportional to the direction and velocity of the mouse drag. We then apply it by adding an impulse to the velocity field using a gaussian “splat”. Other forces such as buoyancy forces for smoke can be also added here.

This next pass computes the pressure field from our velocity field. We then subtract the gradient of it from the velocity in order to satisfy the second equation of Navier-Stokes (zero-divergence). This steps uses a few shader programs. The first one is used to render to texture the divergence of the vector field after forces have been applied. This divergence texture is then passed along with a pressure texture into the Jacobi Iteration shader program from before. The vector field and the newly rendered pressure field are then passed into a gradient subtraction program which renders to texture a vector field with zero divergence.

This is the end of the basic Fast Fluid Dynamics algorithms. However, there are a two more features we added. The first are boundary conditions. This is the feature that makes the window that is rendered to act like the container of the fluid. A fragment shader handles this by adding vectors that point inwards at the boundary pixels of the velocity texture and outwards at the boundary pixels of the pressure texture.

The second add-on we implemented is vorticity confinement. Due to the resolution of the simulation and the numerical error the velocity texture loses the rotational velocity that exist at the edges of flows. The shader program computes the force required to restore an approximation of the lost vorticity.

Now that the final velocity vector field is computed, we apply the advection program to a color texture. This produces the image that gets rendered to the window.

Limitations and Future Work

This simulation can be used to simulate liquids and gasses. In order to get more realistic simulation we can add convection and buoyancy force. Furthermore, we can to simulate smoke and clouds the addition of a gravitational pull to smoke the buoyancy force using a smoke density texture.

THU MAY 14 2020